[Image: Mark Kegans, for the New York Times].

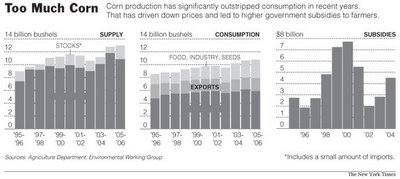

Government subsidies for agriculture in the U.S. are running an estimated $22.7 billion for 2005. These subsidies keep farmers out of bankruptcy, yet they also artificially sustain the market in certain crops, leading to literal mountains of excess grain in the American heartland; this over-supply then depresses the global market price for those grains, making them unaffordable to grow in developing countries, where people actually need the nutrition (and income).

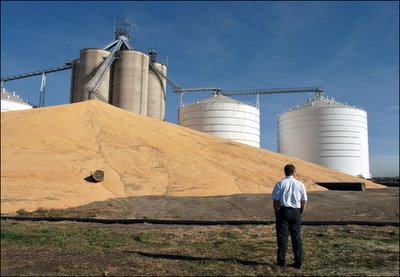

As the New York Times reported last week, Iowa has just made it through a banner year for corn production, "harvesting its second-largest corn crop in history" – and this has produced, yes, "the mega-corn pile."

[Image: Mark Kegans, for the New York Times].

"Soaring more than 60 feet high and spreading a football field wide, the mound of corn behind the headquarters of West Central Cooperative here resembles a little yellow ski hill... At 2.7 million bushels, the giant pile illustrates the explosive growth in corn production by American farmers in recent years" – an excess capacity that has not only lowered the global market price for corn but has inadvertantly produced these strangely Aztec grain-sculptures, otherwise known as corn piles.

[Image: Mark Kegans, for the New York Times].

Due to subsidies, of course – not to mention "a large overhang of grain from last year, coupled with soaring energy costs and two Gulf Coast hurricanes that stymied transportation, and a severe drought that distorted prices" – this could be "the most expensive harvest ever for the federal government."

It's a good thing it's so useful; as the New York Times says, these farmers "could always build a ski lift on the hill."

What's more interesting for me here, however, is not the complicated ins and outs of government farm subsidy programs – to which the Times article is an adequate introduction – but the landscape effects those subsidies have.

Not only are specific landscapes being overproduced – fields of corn vs. fields of wheat; fields of barley vs. fields of sunflowers; etc. – along with all the colors, smells, and sounds those landscapes entail – but the genetic variety of a given region has been artificially determined by the U.S. government.

My point is simply that there seems to be a whole unwritten history of: 1) agricultural micro-evolution as it is affected, or even guided, by government policies, where certain species fare better than others simply because the U.S. government likes them; and 2) the idea of a subsidized landscape.

What would happen, for instance, if it turned out that the head of the Department of Agriculture simply loved sunflowers – or lavender, or cotton? Landscapes of aesthetic usability. Landscapes that just look cool.

Or is the lower Mississippi, as reconstructed and back-levee'd by the Army Corps of Engineers a kind of subsidized landscape? Bought and paid for by Congress?

Or would it be landscapes we already have far too many of and therefore we have to subsidize them – lawns, for example, or mulched playgrounds on hills? You get paid by the government to construct and maintain them.

The national lawn quota of 2006.

Or it's like a Don DeLillo short story: there's a subsidy for airport runways only we've run out of airports to connect them to, so an entrepreneur goes out to South Dakota and buys up land, and he starts building unusable expanses of subsidized runways, prehistoric concrete geometries of overlapping rectangles – and he's paid for it. More than he put in. He profits.

No one ever uses his runways.

It's a kind of aviation landscape subsidy cartel.

Or a car park subsidy... No wonder there are so many.

No comments:

Post a Comment