[Image: Embankment, London, ©urban75].

[Image: Embankment, London, ©urban75].As something of a sequel to BLDGBLOG's earlier post, Britain of Drains, we re-enter the sub-Britannic topology of interlinked tunnels, drains, sewers, Tubes and bunkers that curve beneath London, Greater London, England and the whole UK, in rhizomic tangles of unmappable, self-intersecting whorls.

[Images: The Bunker Drain, Warrington; and the Motherload Complex, Bristol (River Frome Inlets); brought to you by the steroidally courageous and photographically excellent nutters at International Urban Glow].

[Images: The Bunker Drain, Warrington; and the Motherload Complex, Bristol (River Frome Inlets); brought to you by the steroidally courageous and photographically excellent nutters at International Urban Glow].Whether worm-eaten by caves, weakened by sink-holes, rattled by the Tube or even sculpted from the inside-out by secret government bunkers – yes, secret government bunkers – the English earth is porous.

"The heart of modern London," Antony Clayton writes, "contains a vast clandestine underworld of tunnels, telephone exchanges, nuclear bunkers and control centres... [s]ome of which are well documented, but the existence of others can be surmised only from careful scrutiny of government reports and accounts and occassional accidental disclosures reported in the news media."

This unofficially real underground world pops up in some very unlikely places: according to Clayton, there is an electricity sub-station beneath Leicester Square which "is entered by a disguised trap door to the left of the Half Price Ticket Booth, a structure that also doubles as a ventilation shaft."

This links onward to "a new 1 1/4 mile tunnel that connects it with another substation at Duke Street near Grosvenor Square."

But that's not the only disguised ventilation shaft: don't forget the "dummy houses," for instance, at 23-24 Leinster Gardens, London. Mere façades, they aren't buildings at all, but vents for the underworld, disguised as faux-Georgian flats.

(This reminds me, of course, of a scene from Foucault's Pendulum, where the narrator is told that, "People walk by and they don't know the truth... That the house is a fake. It's a façade, an enclosure with no room, no interior. It is really a chimney, a ventilation flue that serves to release the vapors of the regional Métro. And once you know this you feel you are standing at the mouth of the underworld...").

[Image: The Motherload Complex, Bristol – again, by International Urban Glow].

[Image: The Motherload Complex, Bristol – again, by International Urban Glow].There is also a utility subway – I love this one – "with access through a door in the base of Boudicca's statue near Westminster Bridge." (!) The tunnel itself "runs all the way to Blackfriars and then to the Bank of England."

Et cetera.

[Images: The Works Drain, Manchester; International Urban Glow].

[Images: The Works Drain, Manchester; International Urban Glow].My personal favorite by far, however, is also the best-known. (If quite difficult to Google). I'm referring, of course, to British investigative journalist Duncan Campbell's December 1980 piece for the New Statesman, now something of a cult classic in Urban Exploration circles.

What exactly did Campbell do?

[Image: Motherload Complex, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Motherload Complex, Bristol; International Urban Glow]."Entering, without permission, from an access shaft situated on a traffic island in Bethnal Green Road he descended one hundred feet to meet a tunnel, designated L, stretching into the distance and strung with cables and lights." He had, in other words, discovered a government bunker complex that stretched all the way to Whitehall.

On and on he went, all day, for hours, riding a folding bicycle through this concrete, looking-glass world of alphabetic cyphers and location codes, the subterranean military abstract: "From Tunnel G, Tunnel M leads to Fleet Street and P travels under Leicester Square to the then Post Office Tower, with Tunnel S crossing beneath the river to Waterloo."

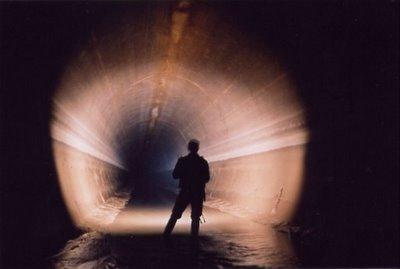

[Image: Like the final scene from a subterranean remake of Jacob's Ladder (or a deleted scene from Creep [cheers, Timo]), it's the Barnton Quarry, ROTOR Drain, Edinburgh; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Like the final scene from a subterranean remake of Jacob's Ladder (or a deleted scene from Creep [cheers, Timo]), it's the Barnton Quarry, ROTOR Drain, Edinburgh; International Urban Glow].Here, giving evidence of Clayton's "accidental disclosures reported in the news media," we read that "when the IMAX cinema inside the roundabout outside Waterloo station was being constructed the contractor's requests to deep-pile the foundations were refused, probably owing to the continued presence of [Tunnel S]."

[Image: Motherload, Bristol; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Motherload, Bristol; International Urban Glow].But when your real estate is swiss-cheesed and under-torqued by an unreal world of remnant topologies, the lesson, I suppose, is you have to read between the lines.

A simple building permissions refusal might be something else entirely: "It was reported," Clayton says, "that in the planning stage of the Jubilee Line Extension official resistance had been encountered, when several projected routes through Westminster were rejected without an explanation, although no potential subterranean obstructions were indicated on the planners' maps. According to one source, '...the rumour is that there is a vast bunker down there, which the government has kept secret, which is the grandaddy of them all.'"

Continuing to read between the lines, Clayton describes how, in 1993, after "close scrutiny of the annual Defence Works Services budget the existence of the so-called Pindar Project was revealed, a plan for a nuclear bomb-proof bunker, that had cost £66 million to excavate."

All of these places have insane names: Pindar, Cobra, Trawlerman, ICARUS, Kingsway, Paddock...

[Image: The Corsham Tunnels; see also BLDGBLOG].

[Image: The Corsham Tunnels; see also BLDGBLOG].Meanwhile – and this is where the dizzying self-intersection begins, systems hitting systems, as layers of the city collide – there is an abandoned Tube station at King William Street, London, but "the only access... is made via the basement of the recently built Regis House," next door – but that "entrance's location" is simply "a manhole in the basement."

It's like a version of London rebuilt to entertain quantum physicists.

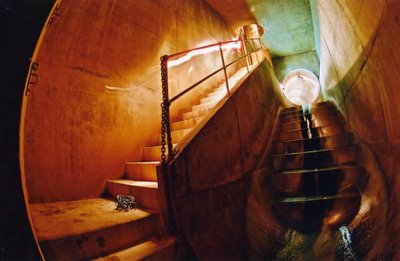

[Images: The freaky stairs and tunnels, encrusted with plaster stalactites, of King William Street].

[Images: The freaky stairs and tunnels, encrusted with plaster stalactites, of King William Street].At one point King William Street's old tunnels "run directly above the existing Bank Northern Line platforms – if you look up you can see directly into these tunnels through several ventilation grilles in the roof." Elsewhere, "the locked entrance to the disused platform was hidden behind some grey panels... making it look like a storage cabinet."

[Image: Belsize Park, from the terrifically useful Underground History of Hywel Williams].

[Image: Belsize Park, from the terrifically useful Underground History of Hywel Williams].Which reminds me of a quotation from one of the links supplied above, referring to a government bunker hidden in the ground near Reading: "Inside, they tried another door on what looked like a cupboard. This was also unlocked, and swung open to reveal a steep staircase leading into an underground office complex."

Everything leads to everything else; there are doorways everywhere.

There is always another direction to turn.

[Image: Main Junction, Bunker Drain, Warrington; International Urban Glow].

[Image: Main Junction, Bunker Drain, Warrington; International Urban Glow].This really could go on and on; there are flood control complexes, buried archives, lost rivers sealed inside concrete viaducts – and all of this within the confines of Greater London.

Then there's Bristol, Manchester, Edinburgh, Kent...

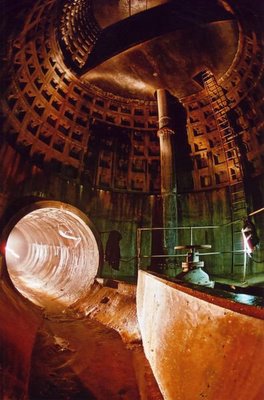

[Image: Wapping Tunnel Vent, Liverpool, by International Urban Glow; a kind of subterranean Pantheon].

[Image: Wapping Tunnel Vent, Liverpool, by International Urban Glow; a kind of subterranean Pantheon].And for all of that, I haven't even mentioned the so-called CTRL Project (the Channel Tunnel Rail Link); or Quartermass and the Pit, an old sci-fi film where deep tunnel Tube construction teams unearth a UFO; or the future possibilities such material all but demands.

Such as: BLDGBLOG: The Game, produced by LucasArts, set in the cross-linked passages of subterranean London, where it's you, a torch, some kind of weapon, a shitty map and hordes of bird flu infected zombies coughing their way down the dripping passages – looking for you...

No comments:

Post a Comment