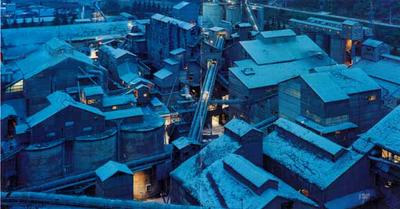

Though the work of Naoya Hatakeyama has just been explored elsewhere, these photographs – entitled Lime Works (Factory Series) (1991-94) – totally blow me away.

For starters, their extraordinary density almost imitates the stratigraphy of the rocks being scraped through –

– even while they document how an increasingly powerful part of the human population interacts with the earth's surface: through highly technical, and very large, digging machines. Entire architectural complexes, instant cities, lit from within and steaming.

They document, in other words, the human interaction with geology.

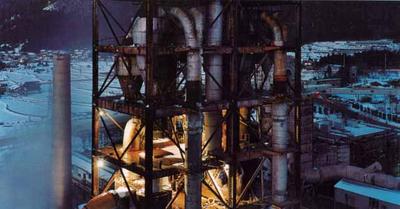

Here, of course, that interaction takes the form of an excavation complex crossed by elevated walkways – and it looks like something straight out of Star Wars –

– or a kind of mineralized King Arthur, ruling from behind a Camelot of mines...

But these photos also bring up the global market in rocks – or the financialization of geology through mineral futures, where taxed and quantifiable fragments of the earth's surface can be traded as commodities on the futures market.

Lime, after all, is a very useful mineral, with entire international associations and Mineral Information Institute reports devoted to its scientific study, value, and market exploitation.

As that latter link informs us, in fact, "Lime has been used for thousands of years for construction. Archeological discoveries in Turkey indicate lime was used as a mortar as far back as 7,000 years ago. Ancient Egyptian civilization used lime to make plaster and mortar."

Meaning, of course, that these photographs show us an architecture of machinery busy digging up a mineral – that will be used by more machinery in the construction of future architecture. (That, in many ways, is the closed loop of the extraction industries: a campsite digging for oil – because its drills need more oil... At some point the whole thing becomes not unlike performance art.)

[Image: A lime works excavation tower seen against the landscape it will soon absorb. If the earth could make horror movies, one wonders if this would be the opening scene...]

I'm left with speculation:

If human beings actually do survive the next ten thousand years; if all this excavation not only continues but accelerates; if usable mineral deposits continue to be found, but only deeper and deeper beneath the earth's surface; then perhaps we might find that we've stripmined every continent below the waterline, returning the earth to the early Devonian, when warm, shallow seas covered most of the planet – only now, or then, the earth will be shelled by a new global city of interlocking excavation architectures – gantry cities, derrick towns, Constant's Babylon –

– complete with feudal rock-salt guilds and a new U.N. of floating lime works factories.

But deep below, in the dark webbing of undersea buttresses, where barrel vaults are covered with scabs of bleached coral, future geologists will be found scuba diving, like Steve Zissou, seeking out new metals and mineral deposits, torch in hand, scouring the outer edge of a flooded earth, diving further and further toward the core.

Then, one day, the digging machines simply put themselves out of business – because the planet has disappeared.

No comments:

Post a Comment